CONSERVATION WORK ON A FAÇADE

The more information you collect from reading a façade (see READING A FAÇADE ), the more difficult it is to make a choice when decisions about its renovation have to be taken. We know very little about the coating of the oldest parts (see IMITATING BRICKS ON BRICKS) and surviving fragments of later coatings can be misleading (thin layers of limewash, for example, extensively applied on the medieval brick curtain wall of the side façade were also present on the chimneys bricked up in the late 19th or even 20th century and were therefore already the result of a “restoration”).

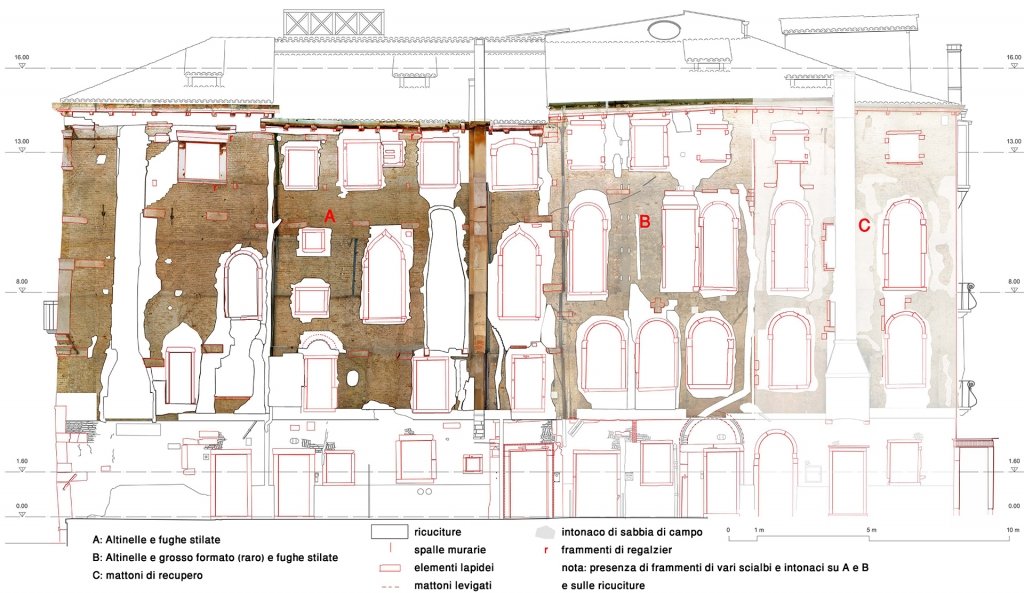

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal during renovation (veniceteam 2012)

The sand and lime mortar present in fragments on the latest part added (see C, figure above) was applied prior to the opening of the 18th century arched windows, while small fragments of ground brick and lime mortar found under the coating dating from 1960 (only in B and C) indicated a render (or a preparation layer of a so-called “marmorino” – a widely used plaster made of lime and stone powder) that is consistent with the 18th century transformation.

Rigid conservation practice calls for the preservation of all “historic” layers (so we should have kept the orange painted plaster from 1960) and restoration theory requires that newly added elements should be recognizable as such (actually the orange plaster was very recognizable as being “modern”…). But fortunately things are more complex: issues about the compatibility of “modern” construction materials with “traditional” ones add technical arguments and the aim of leaving the “history” of the fabric visible adds abstract considerations. If strong evidence of missing parts exists, even reconstruction might be considered (to do justice to the artistic, i.e. aesthetic intentions of the builders). Unmistakably “modern” additions open a Pandora’s box of aesthetic judgments which are usually carefully avoided in conservation work for not being “objective”. There is, in the end, no single standard approach as can be seen from the very different results obtained in recent decades in Venice and abroad.

The various restorations of the façade facing The Grand Canal carried out in the late 19th and 20thcentury illustrate well how the criteria guiding the restorations have changed over time: A photograph taken before 1913 by Naya shows the façade as an example of “Byzantine-Lombard style” covered with plaster decorated with geometrical decorations, marble imitations, and a fake ashlar facing.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata in 1900 (photo Naya) and prior to last renovation (photo veniceteam 2010)

Careful analysis during our restoration revealed that the “Byzantine” arches (stone cladding) were added in the 19thcentury and that the marble cross above the loggia was originally embedded in the side façade (the former Emo property, see * in B, figure above, Palazzo Donà dela Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal during renovation). The decoration of the 19th century plaster underlined this “stylistic” reconstruction: the upper part of the façade in “Byzantine-Lombard style” was decorated with medieval motifs, while the mezzanine-floor and the ground floor with its water gate, both modified in the 16th century, was plastered with fake marble and fake ashlar facing, i. e. typical “Renaissance” decorations.

In the 1930s this plaster, by then considered “fake”, was removed together with the 19th century cast iron balcony and two windows on the top floor were transformed into balconies (the authorization was given on condition that the remaining windowsills were realigned into their medieval position). Exposed brick was aesthetically highly regarded and while the 1930s windows imitated pre-industrial, small-square patterns, only one decade later the windows between the columns of the main floor were replaced by the present large, recessed glass curtain, transforming the formerly narrow balcony into a loggia.

The current renovation has changed the façade on the Grand Canal less dramatically: only an expert eye will notice that two bricked-up windows have been reopened (inserting invisible stainless steel frames for static reasons) and the capitals and twin columns in red limestone from Verona, carefully cleaned and consolidated, reveal layers of red paint applied prior to the 19th century (petrographic analysis done by Lorenzo Lazzarini from IUAV University).

Palazzo Donà della Madonata after renovation and a capital of the twin columns prior to renovation (photo veniceteam 2012 and 2016)

Analysis of the façade at right angles to the Grand Canal (see READING A FAÇADE) motivated a different approach: the part built together with the façade on the Grand Canal was left uncoated in continuation with the façade on the Grand Canal, repointing being confined to the deteriorated areas. Indeed it proved possible to conserve large areas of the original joints between the bricks (these are recognizable by a thin incision) and the transformations described above are still “readable”. The downside is that the surface has to be protected by an invisible hydrorepellent coat that will need periodical renewal.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal after renovation (veniceteam 2016)

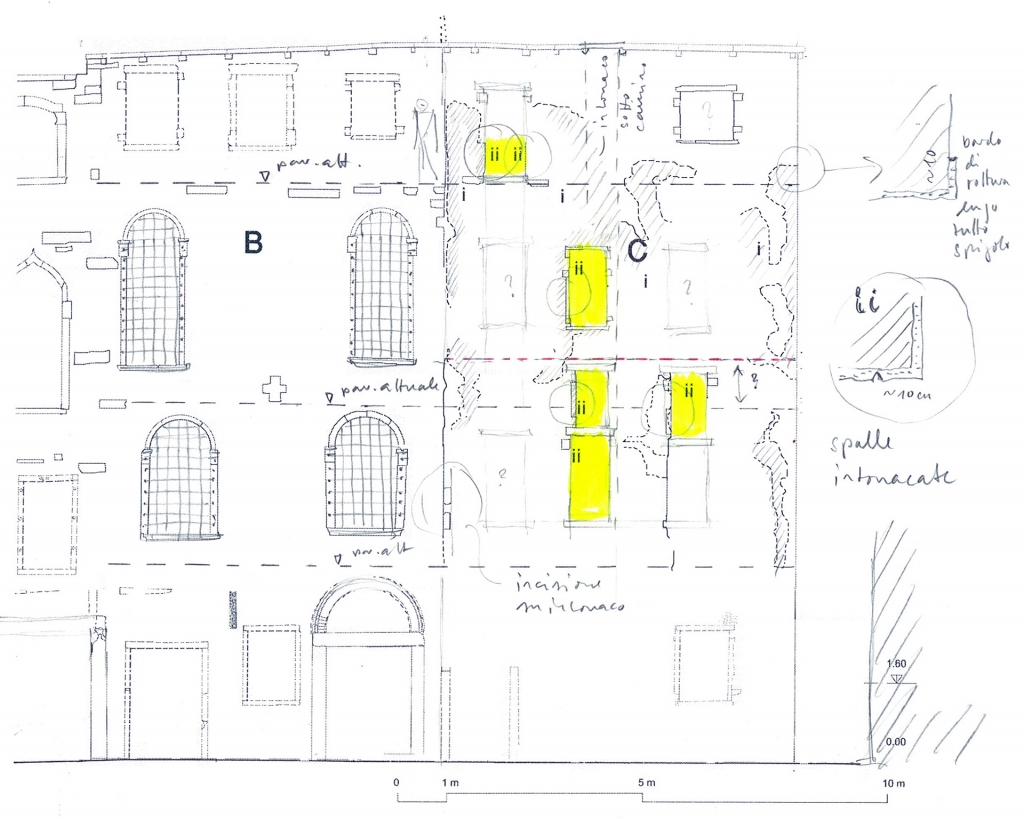

The remaining part of the façade, i.e. the old Emo property and its addition, heavily transformed and unified in the 18th century with the introduction of similar windows and now lost plaster, was covered with a new lime plaster. The latter is compatible with the heterogeneous brick wall but refrains from imitating a “historic” rendering (it contains yellow and grey sand and fragments of red and white limestone from Verona). The now visible imprint of the cross removed in the 19th century and a joint indicate the centre and the limit of the old Emo property prior to 1425. At the special request of the Soprintendenza (Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Tourism) some fragments of the pre-18th century plaster present on the most recently added part of the building were left visible rather than re-covered: an arguable instruction since this plaster was contemporaneous with a completely different layout of the façade, while the new plaster covers the extension of the 18th century transformation and is not the “restoration” of this older fragment as it now appears.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal, survey of bricked-up windows contemporaneous with conserved plaster fragments (veniceteam 2013)

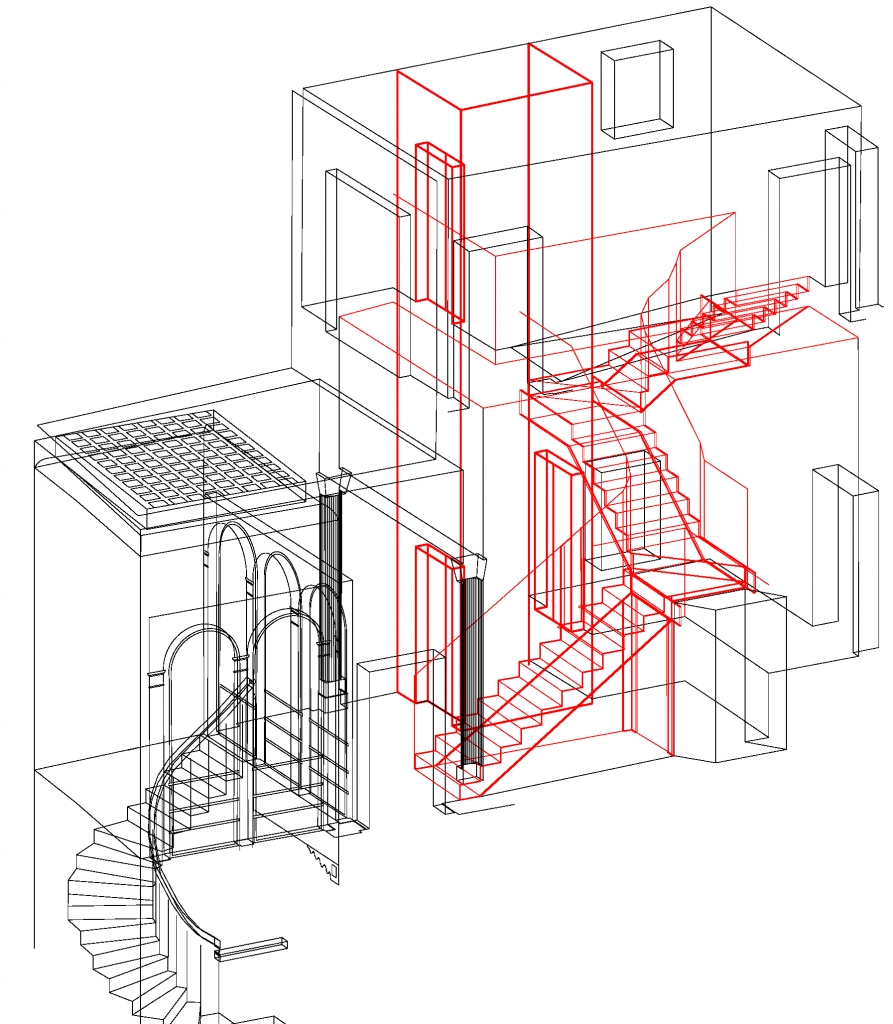

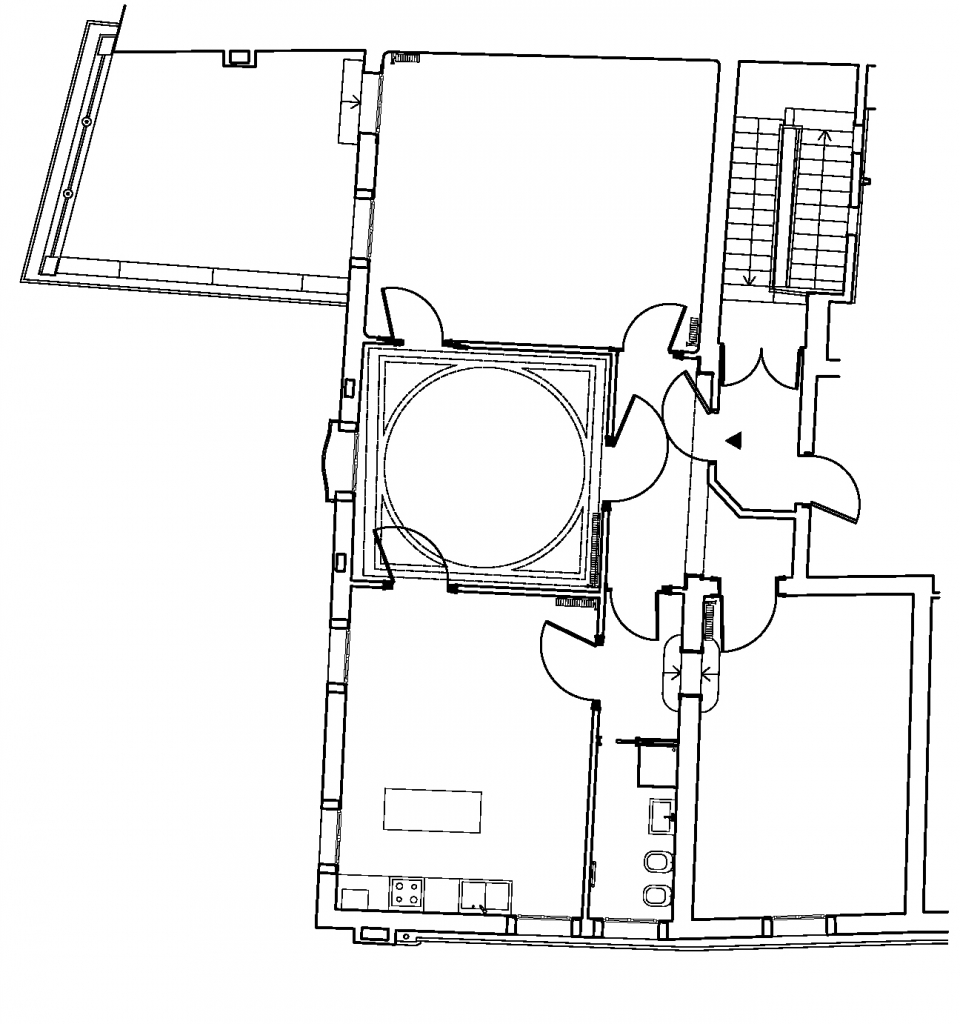

ABOUT MILLIMETRIC TOLERANCE

In 1940 ca. the 19th century staircase of palazzo Donà della Madoneta that occupied a former courtyard was partially demolished to serve only the second floor (piano nobile). To reach the third floor you had to cross the entire building to reach a service staircase at the back. This was possible since the second and third floor had been used as a single, vast apartment at least since 1913. The present owners wanted to be able to use each floor separately again and the elevator from 1965 had to be replaced with a new one, accessible to wheelchairs. Space to comply with the local construction code was extremely limited and only an accurate Total Station survey (closed traverse with an error margin of less than 1mm) made it possible to establish the available space exactly even before demolishing the floor slabs from the 1940s.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, extension of the staircase (veniceteam 2016)

Execution also had to be within millimetric tolerance to allow the handrails of the staircase to run around the elevator tower. To permit precise construction and to distribute the load on the same walls as the previous staircase (to avoid differential settlement since Venetian foundations are unstable, see SINKING HOUSES) a complex metal construction was designed.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, staircase (veniceteam 2014)

The elevator now continues up to the roof terrace and the new landings were conceived as bridges to allow natural light to illuminate the entire new staircase with the existing windows.

A NEARLY PERFECT LAYOUT- Palazzo Soranzo

Good architecture works for centuries. This apartment was created in the second half of the 18th century simply by adding a floor on top of the main façade of a 15th century palace (see BRINGING LIGHT INTO AN OLD PALACE: Palazzo Soranzo)

Palazzo Soranzo, top floor (Verdiana Durand de la Penne 2007)

The ceilings are relatively low (2.4m) and the central drawing-room is smaller than the other rooms, especially considering the floor beneath. The 18th century builder did an unexpected but apt thing: he opened no fewer than three doors in the minute drawing-room creating a 15 m-long visual axis parallel to the façade.

Palazzo Soranzo, top floor (photo veniceteam 2016)

Different floor patterns and delicate decoration in the central drawing-room expand the space even more. As a result this relatively small apartment becomes very generous and the terrace at the side allows the entire apartment to be embraced in a single glance from outside, doubling the already rich spatiality.

Palazzo Soranzo, top floor (photo veniceteam 2016)

Consequently, the restoration was limited to the addition of an open kitchen, the refurbishment of the bathroom and the restoration of the stucco decorations and terrazzo floors.

CONSERVATION PRACTICE IN VENICE

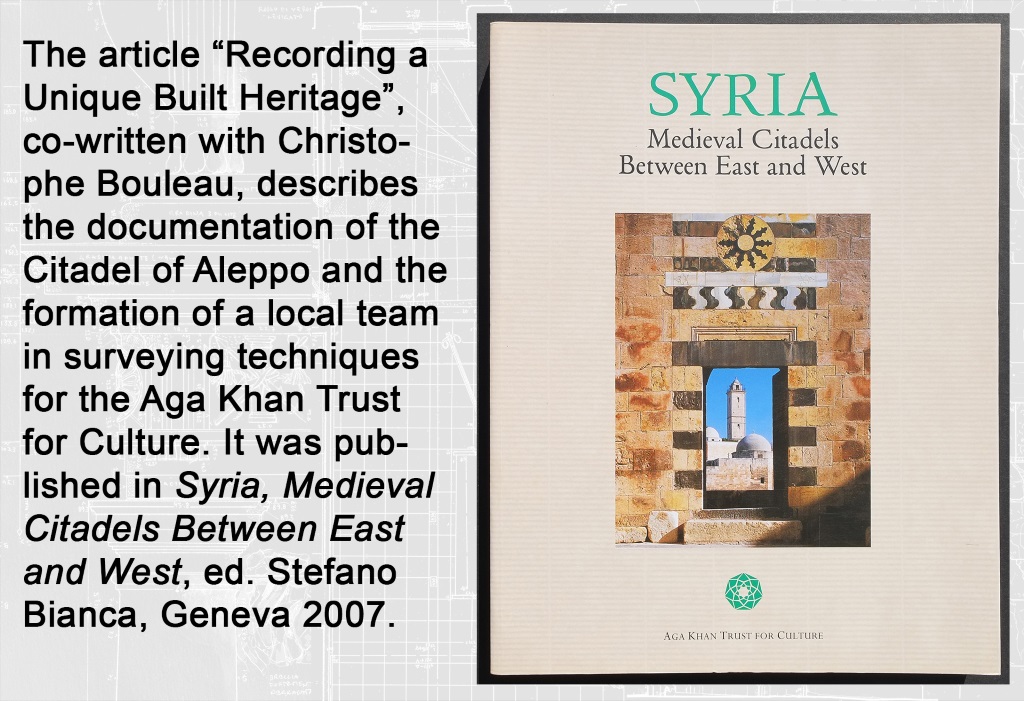

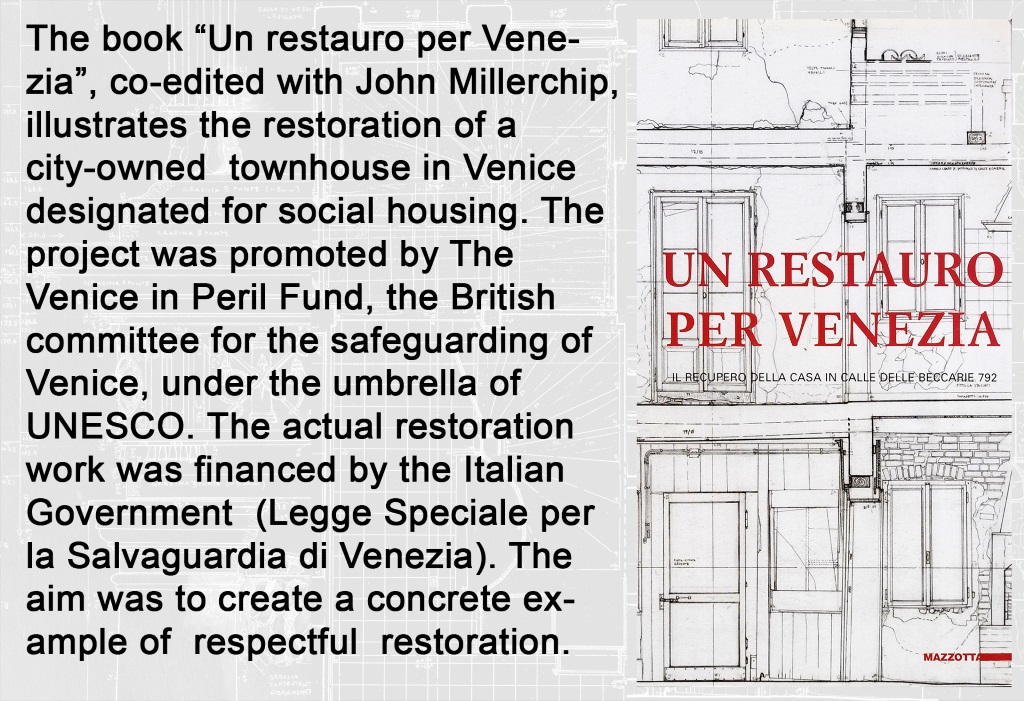

The book “Un restauro per Venezia” , co-edited with John Millerchip, illustrates the restoration of a city-owned townhouse in Venice designated for social housing. The project was promoted by The Venice in Peril Fund, the British committee for the safeguarding of Venice, under the umbrella of UNESCO. The actual restoration work was financed by the Italian Government (Legge Speciale per la Salvaguardia di Venezia). The aim was to create a concrete example of how respectful conservation practice that takes care of the distinctive features of the historic fabric of Venice is possible and financially feasible for social housing. The project is a successful example of collaboration between private funding, public authorities and the University. It was the first time the innovative removal of damaging salt present in the walls was applied on a large scale (see ELIMINATING SOLUBLE SALTS FROM BRICKWALLS).

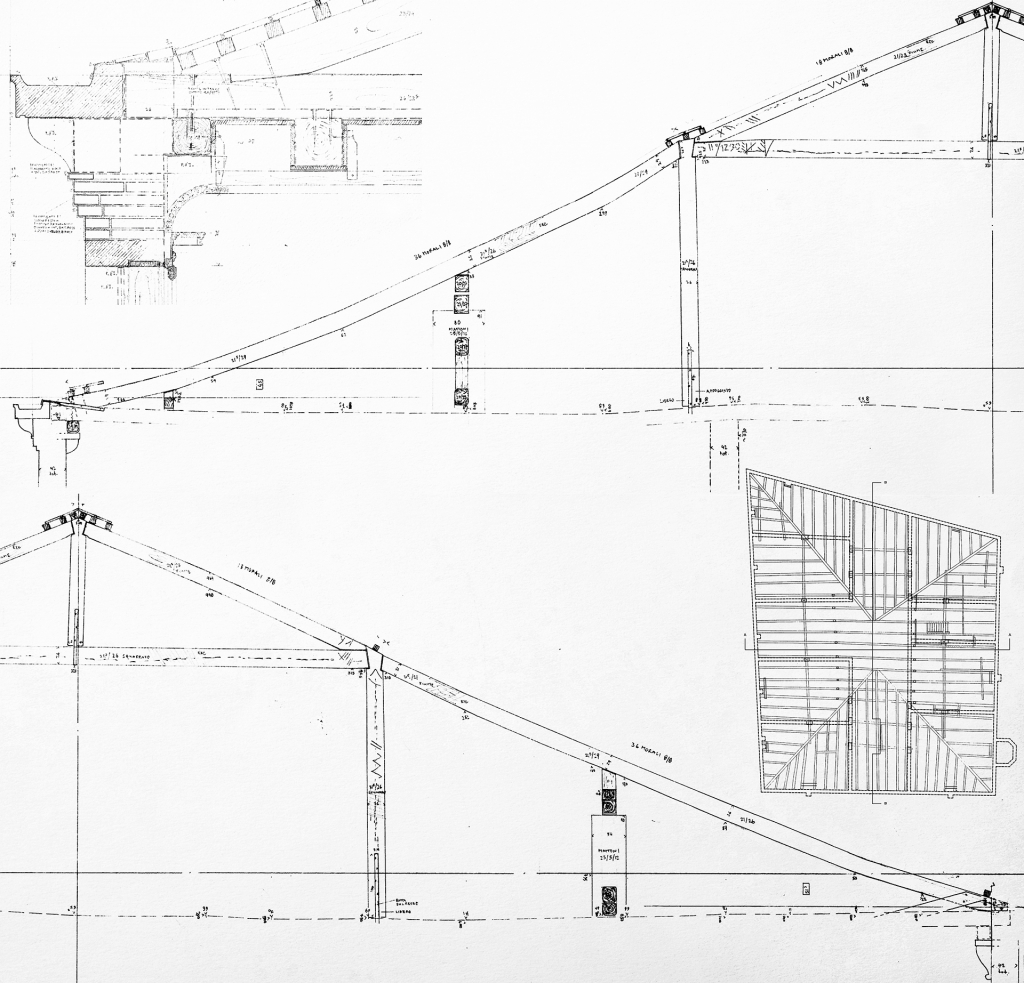

RESTORING ROOFS IN VENICE

Now that zenithal views have become common through the use of drones, and that even in the most remote places on-line aerial views are used for orientating, we should expect more care to be exercised in restoring roofs in historic cities like Venice. Here, over the last 40 years, the very large majority of the pre-industrial handcrafted roof tiles in various shades of brown and red have been replaced with, cheap, orange industrial ones (the old ones are curiously sought-after for covering modern villas in the countryside), not to mention the more or less legal terraces, aerials, parabolic dishes, air-conditioning installations, cell phone aerials, etc.

The roofs of historic buildings in Venice are fascinating: the variously coloured and textured tiles (lead and copper were limited to public buildings and churches) hide complex wooden carpentry, in some cases spanning extremely wide spaces.

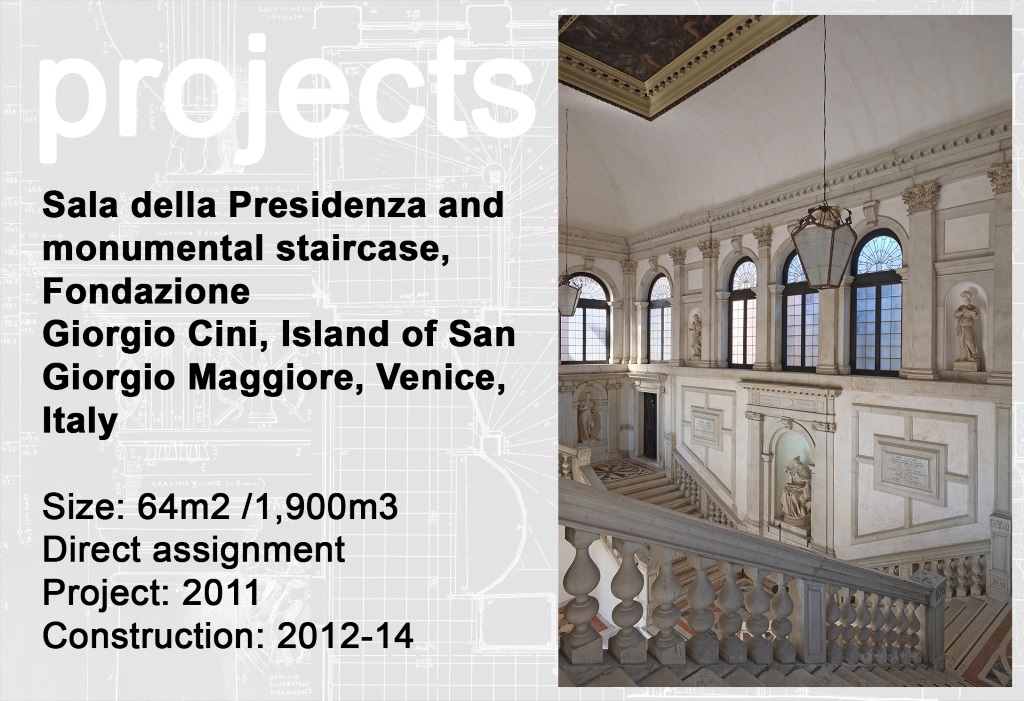

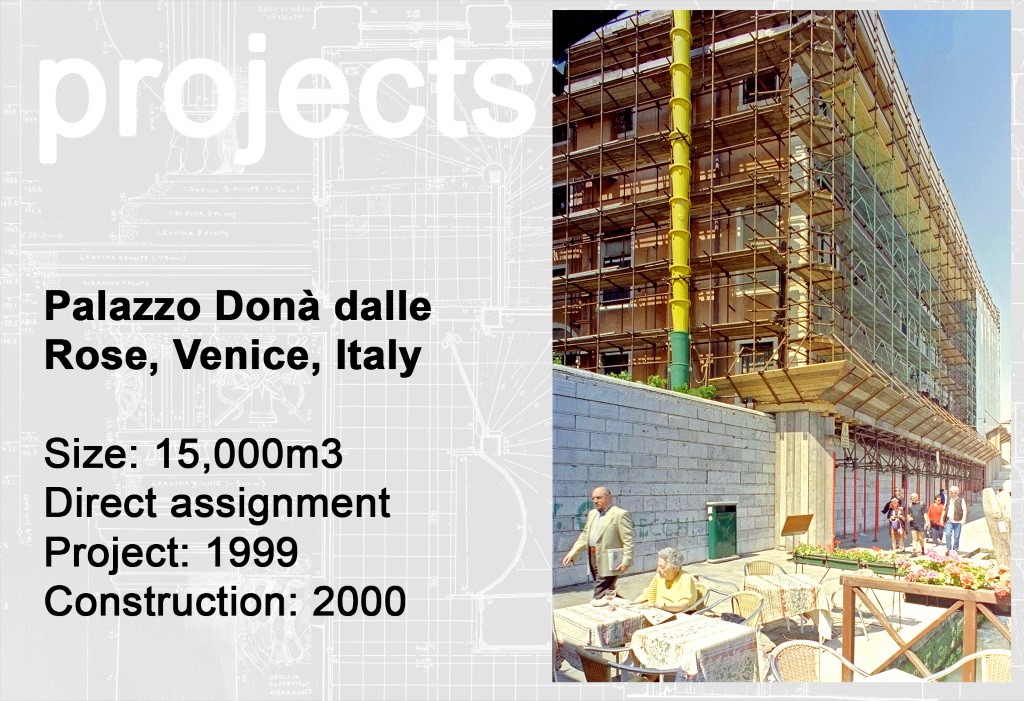

Palazzo Donà dalle Rose, roof during renovation (photo Leo Schubert 2000)

Palazzo Donà dalle Rose was built in the first decade of the 17th century by a doge. He kept very precise accounts and we know exactly how much every part cost. Wood was the cheapest construction material, stone the most expensive. The pine beams and planks were shipped from nearby woods (Cadore), lashed together to form rafts. There were several timber warehouses (one until recently) on the Fondamenta Nuove, the waterfront on which the palace is built.

Palazzo Donà dalle Rose, survey of the roof binders (Leo Schubert 1999)

Palazzo Donà has an interesting T-shaped layout and is very large (1000 sqm per floor): in the central part, the maximum span for the roof binders is 28m, probably amongst the widest ever erected to cover a palace in Venice. The constructional scheme is a traditional triangle with no additional stiffening carried to its structural limits. Reinforcements were in fact added in the past to distribute some of the load onto the walls at right angles to the facades (which are, as usual in Venice, very slender to avoid load concentration on the unstable ground, see SINKING HOUSES) . Beams resting on stone corbels tie the facades together at the top and are firmly connected to the trusses with large nails. The stone cornice that serves as a gutter to collect the rainwater are kept in place with iron tie rods. The rainwater fed a cistern situated on the ground floor (two original internal drainpipes in terracotta are still in place in the north façade). The binders, ca. 1.5m from each other, carry smaller wooden rafters on which thin bricks form the support for the conical roof tiles. These relatively heavy tiles are fixed with mortar and bigger ones were used on the top of the gables.

The restoration undertaken in 2000 had three goals: the repair of structural damage due mostly to rotten wood and rusted iron ties near the gutters, the repositioning of the roof tiles exercising particular attention to reusing the handmade pre-industrial ones (there were sufficient to cover 100% of the visible surface using the new ones underneath), installing a lifeline to allow future maintenance to be carried out safely. This latter installation was the first to be implemented on a private building in Venice long before it became obligatory by law.

Palazzo Donà dalle Rose, roof after renovation (photo Leo Schubert 2000)

ELIMINATING SOLUBLE SALTS FROM BRICKWALLS

Houses in Venice are surrounded by seawater. The soluble salts it contains are the worst enemies for brick, stone and lime mortar. Capillarity transports salt as much as several metres above ground level, where the water evaporates and the salt crystallizes in the pores of the masonry and provokes its destruction. Salt can easily be washed out by immersing single elements into tanks of water, but how can an entire construction be efficiently cleared of salt?

Casa a San Giobbe, washing walls (photo Leo Schubert 2005)

For the successful pilot project of the renovation of a townhouse in Cannaregio, Venice (see CONSERVATION PRACTICE IN VENICE) a pipe system used for irrigation in horticulture was used to wash all the walls up to 4 metres above the ground. The salt concentration dropped from nearly 40g to less than 2g per kilogram of brick wall within a period of 75 days (for a detailed description see Leo Schubert, “La realizzazione del progetto”in Un restauro per Venezia. Il recupero della casa in calle delle Beccarie 792, eds. John Millerchip, Leo Schubert, Milan 2006).

Palazzo Soranzo, washing walls (photo veniceteam 2014)