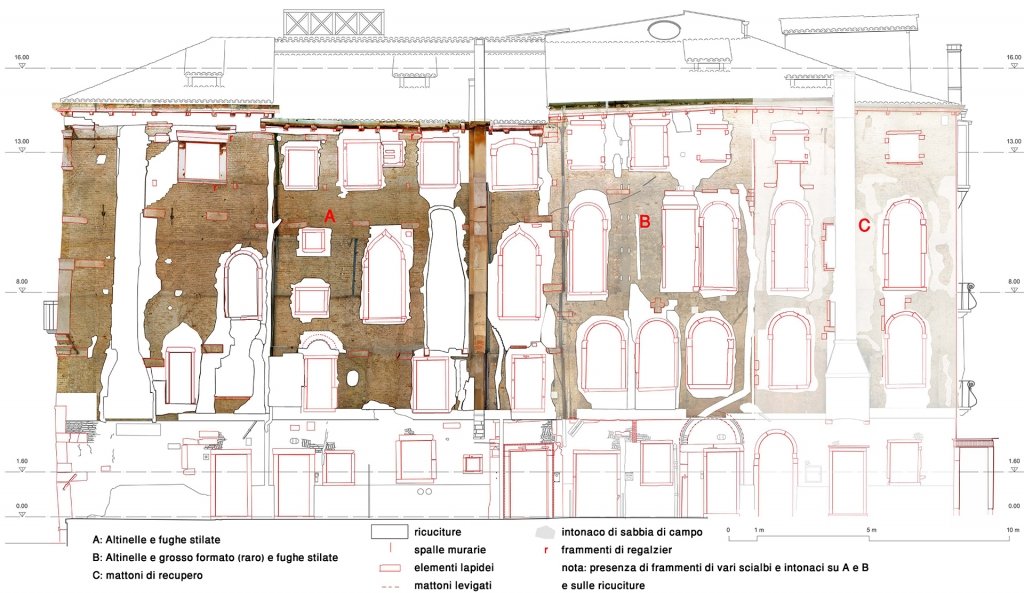

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal prior to renovation (veniceteam 2011)

Historic buildings get transformed with every generation. It is challenging to attempt a mental reconstruction of the form buildings assumed at a precise moment in time or to understand the aesthetic intentions, the constructional constraints or social needs of a historical period (and therefore to position ourselves). Historians ideally try to overlay written or iconographic evidence with archaeological inquiries. Unfortunately, in most cases, only one of these approaches is possible and the interpretation is therefore partial.

Palazzo Donà della Madoneta passed by inheritance through many owners between1425 and the end of the Venetian Republic in 1797. From 1290, the date of the earliest archival document describing a construction in this position on Grand Canal, until 1797, it had never been divided and no legal controversies about its ownership are recorded in the State Archive (special thanks to Jan-Christoph Röessler who did the research). Though few written documents have emerged and only a few sketches, paintings and historic photographs have been found, we can rely on numerous direct observations that emerged during renovation work in order to understand certain aspects of its history.

The now removed plaster on the façade at right angles to the Grand Canal, originally painted orange and dating from 1960, concealed a considerable quantity of information.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal during renovation (veniceteam 2012)

What seemed to be a later addition turned out to be a construction already mentioned in 1425 and owned by the Emo family when they bought the entire block (see B and C, figure above): the part closer to the Grand Canal (B) was built with bricks similar to those used for the structure facing the Grand Canal (A) and might even be older; the rear part (C) was an addition built with reused bricks of different formats. Both have undergone substantial transformation, as shown by closer analysis of the windows and their surrounding walls. During the 16th century 4 arched windows with Renaissance mouldings were inserted into the older part (B)and in the 18th century both parts (B and C) were joined with the addition of 7 arched windows and a cantilevered fireplace. On this occasion, older windows in the rear part (C) were bricked up or covered by the chimney and the Renaissance mouldings (in B) were cut away so that all the windows in B and C matched stylistically.

Unsurprisingly only one of the 28 present windows is still in its “original” place (on the top right in C, see figure above). All the other windows have been bricked up, added or even transformed as seen above. The part facing the Grand Canal (A) retained its stylistically different windows. Here, the only other window contemporary with its surrounding wall was bricked up in the 19th century (the top left window, see figure above, with an architrave actually dating from the XV century) and the two chimneys, one of them still visible in a 19th century photograph, were probably removed as late as the 20thcentury (when central heating was introduced).