The more information you collect from reading a façade (see READING A FAÇADE ), the more difficult it is to make a choice when decisions about its renovation have to be taken. We know very little about the coating of the oldest parts (see IMITATING BRICKS ON BRICKS) and surviving fragments of later coatings can be misleading (thin layers of limewash, for example, extensively applied on the medieval brick curtain wall of the side façade were also present on the chimneys bricked up in the late 19th or even 20th century and were therefore already the result of a “restoration”).

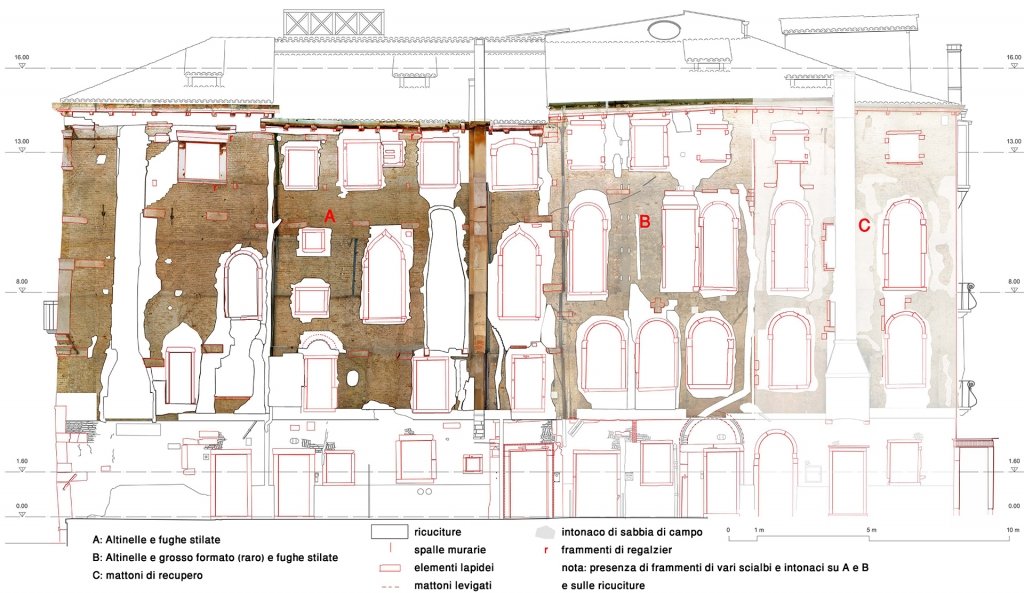

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal during renovation (veniceteam 2012)

The sand and lime mortar present in fragments on the latest part added (see C, figure above) was applied prior to the opening of the 18th century arched windows, while small fragments of ground brick and lime mortar found under the coating dating from 1960 (only in B and C) indicated a render (or a preparation layer of a so-called “marmorino” – a widely used plaster made of lime and stone powder) that is consistent with the 18th century transformation.

Rigid conservation practice calls for the preservation of all “historic” layers (so we should have kept the orange painted plaster from 1960) and restoration theory requires that newly added elements should be recognizable as such (actually the orange plaster was very recognizable as being “modern”…). But fortunately things are more complex: issues about the compatibility of “modern” construction materials with “traditional” ones add technical arguments and the aim of leaving the “history” of the fabric visible adds abstract considerations. If strong evidence of missing parts exists, even reconstruction might be considered (to do justice to the artistic, i.e. aesthetic intentions of the builders). Unmistakably “modern” additions open a Pandora’s box of aesthetic judgments which are usually carefully avoided in conservation work for not being “objective”. There is, in the end, no single standard approach as can be seen from the very different results obtained in recent decades in Venice and abroad.

The various restorations of the façade facing The Grand Canal carried out in the late 19th and 20thcentury illustrate well how the criteria guiding the restorations have changed over time: A photograph taken before 1913 by Naya shows the façade as an example of “Byzantine-Lombard style” covered with plaster decorated with geometrical decorations, marble imitations, and a fake ashlar facing.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata in 1900 (photo Naya) and prior to last renovation (photo veniceteam 2010)

Careful analysis during our restoration revealed that the “Byzantine” arches (stone cladding) were added in the 19thcentury and that the marble cross above the loggia was originally embedded in the side façade (the former Emo property, see * in B, figure above, Palazzo Donà dela Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal during renovation). The decoration of the 19th century plaster underlined this “stylistic” reconstruction: the upper part of the façade in “Byzantine-Lombard style” was decorated with medieval motifs, while the mezzanine-floor and the ground floor with its water gate, both modified in the 16th century, was plastered with fake marble and fake ashlar facing, i. e. typical “Renaissance” decorations.

In the 1930s this plaster, by then considered “fake”, was removed together with the 19th century cast iron balcony and two windows on the top floor were transformed into balconies (the authorization was given on condition that the remaining windowsills were realigned into their medieval position). Exposed brick was aesthetically highly regarded and while the 1930s windows imitated pre-industrial, small-square patterns, only one decade later the windows between the columns of the main floor were replaced by the present large, recessed glass curtain, transforming the formerly narrow balcony into a loggia.

The current renovation has changed the façade on the Grand Canal less dramatically: only an expert eye will notice that two bricked-up windows have been reopened (inserting invisible stainless steel frames for static reasons) and the capitals and twin columns in red limestone from Verona, carefully cleaned and consolidated, reveal layers of red paint applied prior to the 19th century (petrographic analysis done by Lorenzo Lazzarini from IUAV University).

Palazzo Donà della Madonata after renovation and a capital of the twin columns prior to renovation (photo veniceteam 2012 and 2016)

Analysis of the façade at right angles to the Grand Canal (see READING A FAÇADE) motivated a different approach: the part built together with the façade on the Grand Canal was left uncoated in continuation with the façade on the Grand Canal, repointing being confined to the deteriorated areas. Indeed it proved possible to conserve large areas of the original joints between the bricks (these are recognizable by a thin incision) and the transformations described above are still “readable”. The downside is that the surface has to be protected by an invisible hydrorepellent coat that will need periodical renewal.

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal after renovation (veniceteam 2016)

The remaining part of the façade, i.e. the old Emo property and its addition, heavily transformed and unified in the 18th century with the introduction of similar windows and now lost plaster, was covered with a new lime plaster. The latter is compatible with the heterogeneous brick wall but refrains from imitating a “historic” rendering (it contains yellow and grey sand and fragments of red and white limestone from Verona). The now visible imprint of the cross removed in the 19th century and a joint indicate the centre and the limit of the old Emo property prior to 1425. At the special request of the Soprintendenza (Ministry for Cultural Heritage and Tourism) some fragments of the pre-18th century plaster present on the most recently added part of the building were left visible rather than re-covered: an arguable instruction since this plaster was contemporaneous with a completely different layout of the façade, while the new plaster covers the extension of the 18th century transformation and is not the “restoration” of this older fragment as it now appears.

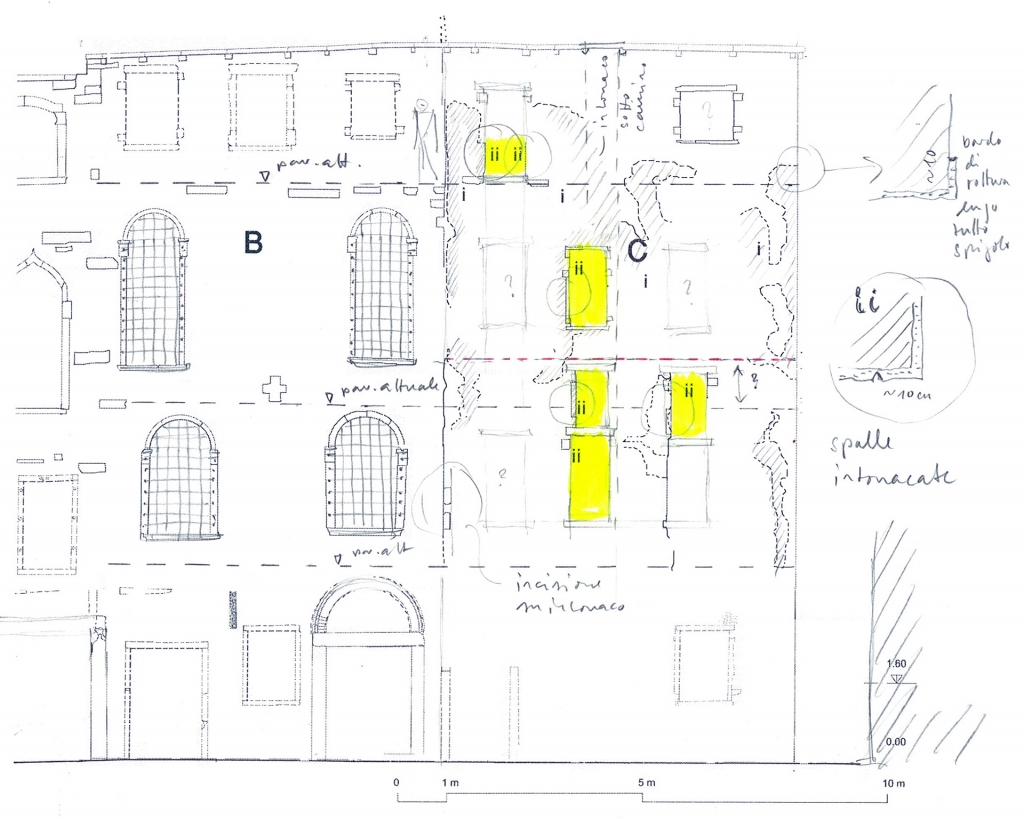

Palazzo Donà della Madonata, façade at right angles to the Grand Canal, survey of bricked-up windows contemporaneous with conserved plaster fragments (veniceteam 2013)