Now that zenithal views have become common through the use of drones, and that even in the most remote places on-line aerial views are used for orientating, we should expect more care to be exercised in restoring roofs in historic cities like Venice. Here, over the last 40 years, the very large majority of the pre-industrial handcrafted roof tiles in various shades of brown and red have been replaced with, cheap, orange industrial ones (the old ones are curiously sought-after for covering modern villas in the countryside), not to mention the more or less legal terraces, aerials, parabolic dishes, air-conditioning installations, cell phone aerials, etc.

The roofs of historic buildings in Venice are fascinating: the variously coloured and textured tiles (lead and copper were limited to public buildings and churches) hide complex wooden carpentry, in some cases spanning extremely wide spaces.

Palazzo Donà dalle Rose, roof during renovation (photo Leo Schubert 2000)

Palazzo Donà dalle Rose was built in the first decade of the 17th century by a doge. He kept very precise accounts and we know exactly how much every part cost. Wood was the cheapest construction material, stone the most expensive. The pine beams and planks were shipped from nearby woods (Cadore), lashed together to form rafts. There were several timber warehouses (one until recently) on the Fondamenta Nuove, the waterfront on which the palace is built.

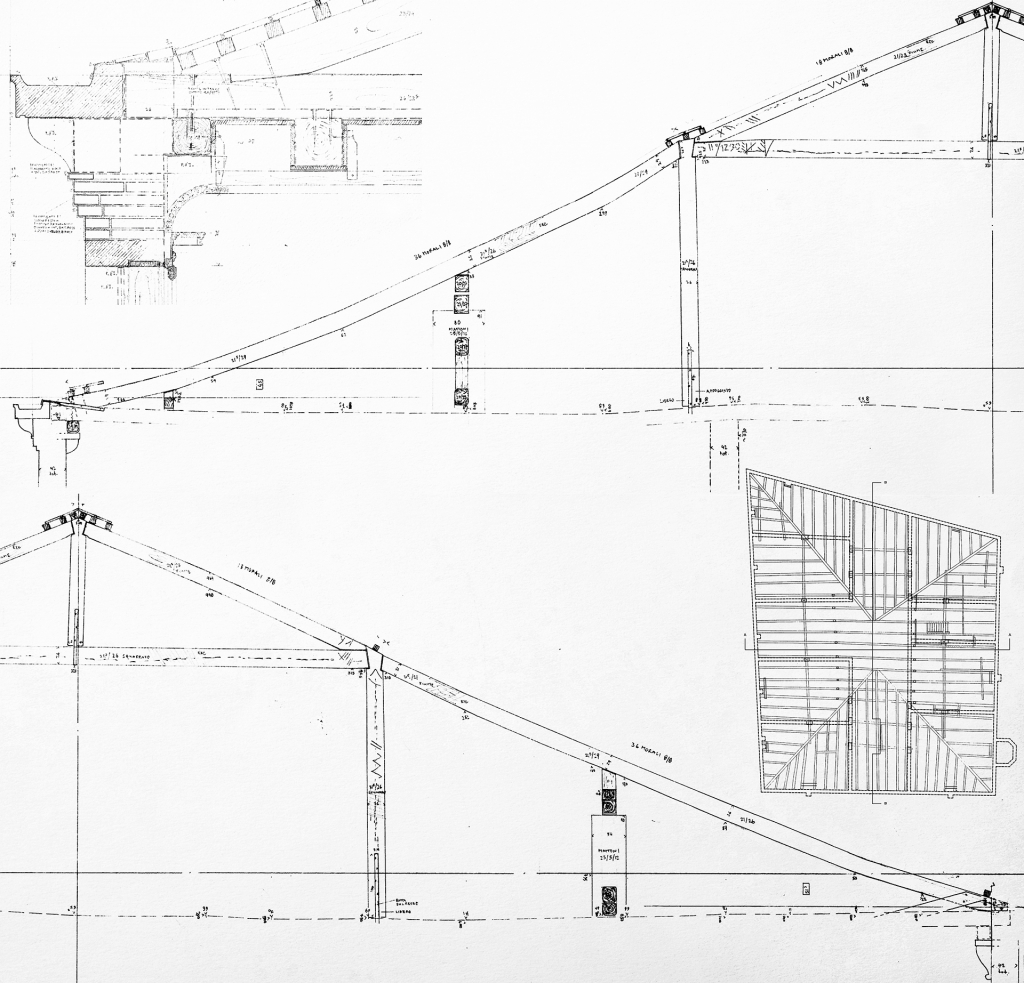

Palazzo Donà dalle Rose, survey of the roof binders (Leo Schubert 1999)

Palazzo Donà has an interesting T-shaped layout and is very large (1000 sqm per floor): in the central part, the maximum span for the roof binders is 28m, probably amongst the widest ever erected to cover a palace in Venice. The constructional scheme is a traditional triangle with no additional stiffening carried to its structural limits. Reinforcements were in fact added in the past to distribute some of the load onto the walls at right angles to the facades (which are, as usual in Venice, very slender to avoid load concentration on the unstable ground, see SINKING HOUSES) . Beams resting on stone corbels tie the facades together at the top and are firmly connected to the trusses with large nails. The stone cornice that serves as a gutter to collect the rainwater are kept in place with iron tie rods. The rainwater fed a cistern situated on the ground floor (two original internal drainpipes in terracotta are still in place in the north façade). The binders, ca. 1.5m from each other, carry smaller wooden rafters on which thin bricks form the support for the conical roof tiles. These relatively heavy tiles are fixed with mortar and bigger ones were used on the top of the gables.

The restoration undertaken in 2000 had three goals: the repair of structural damage due mostly to rotten wood and rusted iron ties near the gutters, the repositioning of the roof tiles exercising particular attention to reusing the handmade pre-industrial ones (there were sufficient to cover 100% of the visible surface using the new ones underneath), installing a lifeline to allow future maintenance to be carried out safely. This latter installation was the first to be implemented on a private building in Venice long before it became obligatory by law.

Palazzo Donà dalle Rose, roof after renovation (photo Leo Schubert 2000)